Reporting For Duty

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Quick Links

Categories

In this Discussion

Some Thoughts On Fleming and Bond...

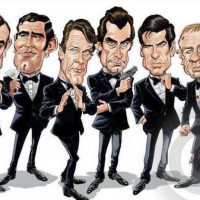

I may be wrong, but James Bond doesn’t have much character, and the little he does have is never truly exploited. He seems to be fastidious, from his clothes and food to how he likes his cocktail. He even takes the adage ‘five a day’ to mean showers instead of vegetables. He’s also tough, snobby and dour. The rest of him is filled in with Fleming’s own attitudes and opinions, to the point where he becomes everything Fleming wished he could have been. Even his reminisces, such as his beach holiday memories at the beginning of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, are Fleming’s, not Bond’s. He appears to be a cipher with aspirations to become a character. In the books, he is an avatar for Fleming, and characterised in the films by whoever plays him – if it’s acerbic Connery or the twinkly-eyed Moore – and, finally, he is our own avatar, our object of self-projection.

The films changed him slightly to make him more appealing to audiences: for example, he is witty – always something people wish they were – and smoother with the ladies. In place of more substantial characteristics, they put crowd-pleasing accoutrements like stunts, gadgets and cars – anything, in other words, to give the audience something to think of when they thought of this soulless cypher dressing alternately like an insurance broker or a guest at a royal wedding.

It seems there’s a great deal of effort by Eon when referring to Fleming’s work (and also by William Boyd in his press interviews for Solo) to make out as though the literary Bond was this deep, tortured character who hates himself more with every killing he causes. It’s become such a cliché to ‘go back to the spirit of Fleming’ that it’s anyone’s guess what it actually means. It sounds commendable, certainly, as is any stated intention by filmmakers to stay faithful to the original source, though it loses credibility when one actually pauses to think what is a spirit of Fleming and, if it’s in the room, is it holding its head in his hands and trying not to look at the Roger Moore section of the DVDs?

Is it the fight with a giant Octopus at the end of Doctor No? Or is it the more serious tone of From Russia with Love, in which Fleming was consciously trying to pen a ‘straight’ spy thriller in the mould of Graham Greene and Eric Ambler? This latter point also addresses another misgiving about his work and that is the unevenness. Despite From Russia…., he was never as serious a writer as John Le Carre or Len Deighton or even Helen MacInnes, who often characterised her work with globe-trotting. Neither is it apparent that Fleming was in possession of a sense of humour. Consequently, he seems to fall between two stools. The repartee of the inherent in the films can be found more readily in The Saint novels, or any of the British thrillers of the 30s and earlier and even as far back as the Bulldog Drummond stories, at which point it turns into Wodehousian whimsy. It was the filmmakers, particularly Terrence Young, who put the wit – as effective, it proved, as the

most lethal gadget – in Bond’s arsenal.

It was also in Drummond – and also the well-intentioned thuggery of Mike Hammer – in which Fleming found the elements he wanted for Bond. The megalomaniacal villains, meanwhile, can readily be sourced in Drummond’s nemesis Carl Peterson, Dr Fu Manchu, any number of high-minded rascals pitting themselves against Simon Templar, the rogues’ gallery of Sexton Blake villains and, in particular, Jules Verne’s atomic bomb thrillers Robur the Conqueror and Facing the Flag.

Despite such weak-footed derivation – other writers, after all, were making repeated visits to the same well, such as Desmond Cory, James Leasor, and a young Dennis Wheatley – it is Fleming who remains, thanks in no small part to the franchise which has constantly reminded audiences of the character he created. It is a sort of pseudo-snobbery, of course, in which some people disparage the films in favour of the books. This happens with almost all books, of course, as it currently is with Game of Thrones/A Song of Ice and Fire. The same continues to happen with Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, if not Agatha Christie’s Poirot. There’s an implication by such zealots that while brain-dead cinema-goers can chortle and cheer at the films – which, with their spectacular stunts and set-pieces, can almost be likened to the expertly-synchronised antics of a circus – it takes a mature and sensitive mind to appreciate the deep character that is the literary Bond. He is, supposedly, the object of a nationalistic double-standard, a government-funded killer who is forced to be as bad as the bad in order to overthrow them. But although such paradoxes are possible and even justified, they are never sufficiently addressed by Fleming to make them discernable in the actual novels. Instead, Fleming is too busy navigating his avatar towards the nearest dinner table to over-indulge on – of all things – scrambled eggs, or mutter something condescending about socialists.

Much has been made of the prevalent branding – perhaps the earliest product placement known to fiction – and the effect it must surely have had on the ration-bound British public. Indeed, Casino Royale was published a mere year before rationing ceased. It is perhaps Fleming’s claim to originality, aside from the ‘sex and sadism’ which has followed the books around like a secret agent stalking his target. While Fleming enjoyed fine food, it is doubtful that Fleming was fettishistic – as it is doubtful that he too slept with a gun under his pillow – and it can surely be seen as part of the same languid, occasionally frenetic, daydream his character drifts through. The sadism angle is curious in itself, as such sensationalism is usually the hallmark of pulp fiction, and despite the garish paperback Pan covers, the Bond books managed to be too ostentatious to be sensational and not literary enough to be treated respectfully all at the same time.

Despite this, it must be remembered, these books were major best-sellers in their time, even if their apparent immortality is perhaps undeserved. Their transformation from pulp to prestige is complete: from being available for the price of a packet of cigarettes at a newspaper stand and read with the cover turned back on the train from Paddington Station, to their present existence as ‘Penguin Classics’, read as audio books or performed for radio by respected thespians trying to convince themselves it is more savoury than that Man With the Golden Gun repeat they caught the previous afternoon. Furthermore, as played by Dominic Cooper, Fleming is perceived how he always wanted to be, as a Bond-like war hero, in the BBC mini-series. Ironically, after such ashamed belittling from his wife and her society friends, and even his own self-effacing flippancy, Ian Fleming and his novels are almost respectable.

The films changed him slightly to make him more appealing to audiences: for example, he is witty – always something people wish they were – and smoother with the ladies. In place of more substantial characteristics, they put crowd-pleasing accoutrements like stunts, gadgets and cars – anything, in other words, to give the audience something to think of when they thought of this soulless cypher dressing alternately like an insurance broker or a guest at a royal wedding.

It seems there’s a great deal of effort by Eon when referring to Fleming’s work (and also by William Boyd in his press interviews for Solo) to make out as though the literary Bond was this deep, tortured character who hates himself more with every killing he causes. It’s become such a cliché to ‘go back to the spirit of Fleming’ that it’s anyone’s guess what it actually means. It sounds commendable, certainly, as is any stated intention by filmmakers to stay faithful to the original source, though it loses credibility when one actually pauses to think what is a spirit of Fleming and, if it’s in the room, is it holding its head in his hands and trying not to look at the Roger Moore section of the DVDs?

Is it the fight with a giant Octopus at the end of Doctor No? Or is it the more serious tone of From Russia with Love, in which Fleming was consciously trying to pen a ‘straight’ spy thriller in the mould of Graham Greene and Eric Ambler? This latter point also addresses another misgiving about his work and that is the unevenness. Despite From Russia…., he was never as serious a writer as John Le Carre or Len Deighton or even Helen MacInnes, who often characterised her work with globe-trotting. Neither is it apparent that Fleming was in possession of a sense of humour. Consequently, he seems to fall between two stools. The repartee of the inherent in the films can be found more readily in The Saint novels, or any of the British thrillers of the 30s and earlier and even as far back as the Bulldog Drummond stories, at which point it turns into Wodehousian whimsy. It was the filmmakers, particularly Terrence Young, who put the wit – as effective, it proved, as the

most lethal gadget – in Bond’s arsenal.

It was also in Drummond – and also the well-intentioned thuggery of Mike Hammer – in which Fleming found the elements he wanted for Bond. The megalomaniacal villains, meanwhile, can readily be sourced in Drummond’s nemesis Carl Peterson, Dr Fu Manchu, any number of high-minded rascals pitting themselves against Simon Templar, the rogues’ gallery of Sexton Blake villains and, in particular, Jules Verne’s atomic bomb thrillers Robur the Conqueror and Facing the Flag.

Despite such weak-footed derivation – other writers, after all, were making repeated visits to the same well, such as Desmond Cory, James Leasor, and a young Dennis Wheatley – it is Fleming who remains, thanks in no small part to the franchise which has constantly reminded audiences of the character he created. It is a sort of pseudo-snobbery, of course, in which some people disparage the films in favour of the books. This happens with almost all books, of course, as it currently is with Game of Thrones/A Song of Ice and Fire. The same continues to happen with Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, if not Agatha Christie’s Poirot. There’s an implication by such zealots that while brain-dead cinema-goers can chortle and cheer at the films – which, with their spectacular stunts and set-pieces, can almost be likened to the expertly-synchronised antics of a circus – it takes a mature and sensitive mind to appreciate the deep character that is the literary Bond. He is, supposedly, the object of a nationalistic double-standard, a government-funded killer who is forced to be as bad as the bad in order to overthrow them. But although such paradoxes are possible and even justified, they are never sufficiently addressed by Fleming to make them discernable in the actual novels. Instead, Fleming is too busy navigating his avatar towards the nearest dinner table to over-indulge on – of all things – scrambled eggs, or mutter something condescending about socialists.

Much has been made of the prevalent branding – perhaps the earliest product placement known to fiction – and the effect it must surely have had on the ration-bound British public. Indeed, Casino Royale was published a mere year before rationing ceased. It is perhaps Fleming’s claim to originality, aside from the ‘sex and sadism’ which has followed the books around like a secret agent stalking his target. While Fleming enjoyed fine food, it is doubtful that Fleming was fettishistic – as it is doubtful that he too slept with a gun under his pillow – and it can surely be seen as part of the same languid, occasionally frenetic, daydream his character drifts through. The sadism angle is curious in itself, as such sensationalism is usually the hallmark of pulp fiction, and despite the garish paperback Pan covers, the Bond books managed to be too ostentatious to be sensational and not literary enough to be treated respectfully all at the same time.

Despite this, it must be remembered, these books were major best-sellers in their time, even if their apparent immortality is perhaps undeserved. Their transformation from pulp to prestige is complete: from being available for the price of a packet of cigarettes at a newspaper stand and read with the cover turned back on the train from Paddington Station, to their present existence as ‘Penguin Classics’, read as audio books or performed for radio by respected thespians trying to convince themselves it is more savoury than that Man With the Golden Gun repeat they caught the previous afternoon. Furthermore, as played by Dominic Cooper, Fleming is perceived how he always wanted to be, as a Bond-like war hero, in the BBC mini-series. Ironically, after such ashamed belittling from his wife and her society friends, and even his own self-effacing flippancy, Ian Fleming and his novels are almost respectable.

^ Back to Top

The MI6 Community is unofficial and in no way associated or linked with EON Productions, MGM, Sony Pictures, Activision or Ian Fleming Publications. Any views expressed on this website are of the individual members and do not necessarily reflect those of the Community owners. Any video or images displayed in topics on MI6 Community are embedded by users from third party sites and as such MI6 Community and its owners take no responsibility for this material.

James Bond News • James Bond Articles • James Bond Magazine

Comments

Seriously?

Anyway, moved from News to Literary 007, although I appreciate this covers literary and movies.

Shortly after I had joined here I argued in another thread, that it is that easy to get into an argument about Bonds character because he has so little we actually can refer to as a given. He muses about how woman are just for pleasure and just a disturbance otherwise yet falls in love with just about any woman he meets in the books. He is called a true professional and wonderful machine by Mathis, but doesn't give a second thought when he gets a package with something ticking inside and rather continues having breakfast instead (one wonders what standard of professionalism the French might have).The list is endless. Of course all I got back then were quite a few insulting suggestions. I sincerely hope, that your essay doesn't share the same fate,even though TakeAsips comment would suggest otherwise.

In The Durable Desperadoes By William Vivian Butler his "critical study of some enduring heros", published by MACMILLAN in 1973, is another fine source of material regarding the genre of the Gentleman Outlaw. It has a ton of Saint material, and other saint-like creations such as Raffles, The Toff, Arsene Lupin, Bulldog Drummond, and more... contains a lot about the influences on Ian Fleming and his ultimate hero.

Well worth a read if you can find a copy

The Durable Desperadoes is an amazing book, indeed, SaintMark. It's well-written while managing to be witty and conversational at the same time - it could well be seen as one of the very first fan-site articles. Butler really knew his topic, having grown up with the 1930s gentlemen outlaws, and makes many terrific observations on The Toff, The Baron, Norman Conquest etc and particularly The Saint and his half a dozen character-developments across the years.

And a book that contains a chapter better read by anybody liking James Bond and Ian Fleming.

That said,in my not so humble opinion, there is one great omission in his assessment of Fleming's characterisation of Bond and that is that Ian wrote him as men of a certain class would describe other men at that time. The 'stiff upper lip' still reigned supreme and aspects of character could be alluded to whilst maintaining a decorum.

Fleming's Bond was a product of the '50s and very early '60s in terms of character evolution. The progression from the characterisation of the super heroes from Buchan, Sapper and Charteris was to introduce a certain darkness, promiscuous sex and a level of violence that had only, up until then, been brokered by the American pulp writers, notably Spillane.

When Terence Young came along and elevated the irony, it was to develop the character for the sixties and the Beatles generation.

My contention would therefore be that Bond didn't suffer from lack of characterisation. It was simply that he got a portrayal that was innovative at that point in time. Clearly the game has moved on and in truth, this is probably why the continuation authors struggle to make Bond relevant.

A very fine essay, @DJDave. Well done! Don't listen to any detractors as of course they could never write anything remotely like this themselves. Jealousy is a terrible thing.

And yes, @SaintMark, you are right about Butler's book. I got a copy recently and it is required reading for all addicts of the thriller genre.

You are wrong. Bond is not a deep or extremely complicated character, but he has more character than you say, and as I delineate later on. True, as a heroic character in a thriller, room must be left for reader self-identification, so Bond is not filled-in to the degree of, say, Hamlet.

You're cheating though. If an author fills in a character with parts of his personality and characteristics, that counts toward the content and depth of a character. To discount characterization by saying "oh, that's just bits of the author intruding" is bizarre and alien to the concept of fiction. Yes, as John Pearson said, Bond is Fleming "daydreaming about himself in the third person." But no one confuses Fleming with Bond--the latter is different enough from his creator, and the creation of a separate dream self is an achievement in itself.

How do you know? Again, cheating. What makes those memories not Bond's? An author is perfectly entitled to draw on his own experiences and memories and reworking them into fiction.

Yes, and it's also Bond debating the nature of evil with Mathis in CR, or grieving over Vesper's death and vowing to leave routine espionage to "the white collar boys." It's Bond being overcome with melancholy when he bids a permanent goodbye to Gala Brand. It's Bond having a long, amused discussion on marriage and love with Tiffany Case, to whom Bond realizes he must act as much as a therapist as a lover. It's Bond sitting in an airplane and disgustedly realizing he's "pimping for England" and looking back on his younger self and wondering if it would approve of the adult Bond. It's Bond reflecting on life and death in an airport lounge in Miami and dealing with remorse for causing the death of a man whose life he knew to be worthless. It's Bond worrying if he's committing a private execution for M’s benefit in FYEO. It's Bond realizing how little his life means compared to the everyday drama in Quantum of Solace. It's Bond mourning for the fish who die in "The Hildebrand Rarity." It's Bond giving his winnings from Goldfinger to Jill Masterton, and feeling a wave of nausea later on when he learns from Tilly that he was responsible for her death. It's Bond looking at himself in the mirror after a hangover and calling himself a bastard. It's Bond sitting entranced through Domino's long story about the logo on Player's cigarettes. It's Bond being kicked out of bed by Tracy and being told he's a lousy lover. It’s Bond falling to drunken pieces after the death of his wife and blaming himself for her death. It's Bond deliberately disobeying his orders and refusing to kill a female assassin, telling his minder that he doesn’t care if he gets fired and would even be grateful for it. It's Bond being unable to kill Scaramanga in cold blood. It's Bond refusing a knighthood because he can't take himself seriously as a knight.

How many of these touches of character were in the movies? No more than a few, and the movies were better off for them. Pointing to the difference between the Ambler-like FRWL and the Rohmer-like Dr.No is pointing to one of Fleming's strengths, not weaknesses--his range easily stretched from one extreme of the thriller genre than another.

I don't see how Fleming was any less serious than those writers. It takes as much seriousness to write a book that relies on the fantastic, like Dr. No, as it does to write FRWL or a Deighton book. Your argument relies on an argument from authority-- because many snobbish middlebrow critics regard Le Carre and Deighton as inherently more "serious," they become the definition of the term.

This is one of the oldest and falsest cliches around: "Fleming has no sense of humor and the movies had to supply it." It's false. You can find plenty of witticisms and humor in books like GF and You Only Live Twice, and while the earlier Bond books are lighter in humor, it's still there--even the grim Casino Royale has Bond exchanging obscenities with a bartender, and Diamonds Are Forever has plenty of wisecracks from Tiffany Case. Beyond all this, I've never met anyone who thinks the books would have benefited from the sort of one-liners beloved by the movies (on the other hand, plenty of people wish some Bond films had a little less humor). On the page, Fleming had to work hard to make implausible things plausible. On screen, that happens before your eyes and can threaten to overload the viewer--that's why the films added one-liners to lighten the impact of a particularly spectacular or violent scenes. Such humor would have been a mistake in the books.

Megalomaniacal villains have existed since before Prof. Moriarty. Pointing out a few doesn't really say anything. Fleming's villains are distinguished by a set of characteristics that, taken together, make them his own. They are usually physically grotesque, and Fleming's fascination with physiognomy is all his own--hence the pupils entirely surrounded by white, the red hair, hearts on the wrong side of the body, pincer-hands, botched and successful plastic surgeries, yellow or red eyes, football heads, etc. They are usually men of immense power and means, and often belong to organizations arisen from the cold war, such as Smersh (a "real" organization that Fleming re-invented) or Spectre (one of Fleming's most innovative concepts--a freelance terrorist group). They also tend to wine-and-dine Bond, thus enforcing the high-living feel of Bond's world. And they are often twisted father (or mother) figures--as seen in the disturbing scene of LeChiffre lecturing Bond like a schoolboy while torturing him. That is uniquely Fleming.

It's less pseudo-snobbery than common sense. Sherlock Holmes is the most filmed screen character in history, yet most would agree that the majority of films featuring him aren't very good, either as films or adaptations. That's what happens when a character which derives its uniqueness from the specific personality of one author is diluted by the process of assigning teams of corporate employees to produce adaptations of the original stories.

No. I think what many "zealots" would say is that the Bond films turned into formulaic self-parodies which relied on a checklist of ingredients ("sacrificial bed-mate" etc). Bond's character was vulgarized and exaggerated as well--book Bond is not a wine snob, but you wouldn't know that from his foppish screen counterpart. Additionally, the formulaic films excised many of the scenes of doubt, fear, or melancholy that helped make the literary Bond a more interesting character (compare the book and film of Moonraker--the former is a thriller with a very human ending, the latter is a cartoon). The Dalton and Craig films have tried to re-humanize the character and make the films less formulaic by drawing on the books, and the Bond film series as a whole has usually returned to the books after drifting too far into self-parody (hence the films of OHMSS, FYEO, TLD, CR--all of which undeniably owe much to their literary sources). Fleming had a limited set of character types and situations, but he wasn't one of those authors who writes the same book over and over again (has anyone confused GF with TSWLM?). The Bond films on the other hand tend to blend into each other.

What novels have you been reading? Bond's ethical qualms are discernible enough in CR, GF, FYEO, TLD, and TSWLM, and even Blofeld calls attention to them in YOLT. It's also inaccurate to say that Fleming was saying Bond was "forced to be as bad as the bad"--Bond continually operates on a higher moral plane than any of the villains. He is not a murderer or torturer or sadist. The books continually depict the Secret Service as being a more honorable organization than those of the Russians or Spectre.

That is another incorrect cliche--the Bond books are never "pulp" and were not considered such during their original publication. They were brought out for "an A readership" (in Fleming's words) and respectfully reviewed in publications like The Times Literary Supplement. They were treated as part of the thriller genre, which was looked upon with more respect than, say, science fiction, thanks to writers like Ambler and Greene and Buchan.

On what planet? The majority of articles published on Fleming tend to be belittling or focused on attacking his misogynism/imperialism/racism. And whenever someone like Faulks or Boyd writes a Bond pastiche, literary critics who judge solely on reputation reassure us that the new books are of course much better than anything Fleming could write. (See the recent articles on Fleming in publications like The Atlantic or The Guardian.) Fleming is very far being respected or respectable. You are arguing against a chimera, and ironically perpetuating what you claim is lessening.

Thank you to everyone for their comments. I wrote it to see if I had the whole thing the right way round, and welcome everyone's opinion, one way or the other.

I also don't buy this he was never as serious a writer as John Le Carre business. I love Le Carre, but they are just taking a different approach. His plots and characters may be more serious - yes; but a more serious writer? No Sir. Just ask any of these fine authors too: http://literary007.com/quotes-on-the-books/

As far as He seems to be fastidious, from his clothes and food to how he likes his cocktail., the truth is Fleming was none of these - just ask Noel Coward! I find it rather impressive that Fleming was able to infuse Bond with this knowledge.

However, fair play for sticking your neck out and inviting debate. One hopes the literary 007 category on this forum always maintains a high level of decorum and respect.

A few of my own thoughts:

1. The greatest thing Fleming gave to Bond was his ability to lace the seriousness of death with the ecstasy of life. That's what he brings that others can't.. the sensationalism of eating, smoking, visiting, and sleeping with the best, all behind the silent strength and brutality required by the work of espionage; to beat, torture, stalk, and murder.

2. You mention Bond fighting an Octopus in Dr. No as Fleming stretching out the realism that other espionage novels pride themselves on maintaining. You then follow that comment with a mention of From Russia With Love. Ironically, Bondmania exponentially grew when President John F. Kennedy put From Russia With Love on a list of his favorite books; a President which had been a sailor who had managed to survive the sinking of his ship and watched as his fellow crew members were eaten alive in the shark infested waters. To a guy like that, an Octopus battle is easily a credible scenario.

3. Fleming let Bond have fun. I could agree with an argument that he made Bond into a cypher, and likely filled in emotions, thoughts, and memories from his own experiences. The important thing he did with Bond, though, was send Bond on experiences and to places he could only dream of, and leaving just enough space for the reader to fit into Bond's character. When you read Fleming's Bond, your reading the dreams of a spy, written with the knowledge of a scenario aficionado, with the imagery of your world.

Let me in turn congratulate you on having produced such a well-written piece. I initially thought you had reposted a magazine article! That's how professional it looked. There was a recent piece in the Atlantic that attempted to claim the literary Bond had no character, and it was hugely inferior to your article.

And I sympathize with several of your points. Fans are wrong to claim that the literary Bond is a complex character. He's just more human in his range of emotions than his screen counterpart has usually been. Kingsley Amis best explained how Bond's character is left open enough for audience identification but sketched-in enough to suggest a degree of inner life. It's Bond's melancholia--his Byronic side, as Amis put it--that makes him human and likable. The movies mostly neglected that. That said, Fleming is not Tolstoy. His characters are drawn with strong outlines and relatively little shading. Or, to compare novelists with comic strip artists, if Graham Greene is equivalent to an illustrative master like Alex Raymond, Fleming is like Chester Gould and works with strong lines and chiaroscuro.

I also get slightly irritated when I hear the modern-day Bond filmmakers boast about how they've returned to "Fleming's Bond." I consider the film of Casino Royale to be more faithful to the letter of the novel than to its spirit (and the idea of a cocky, rebellious rookie Bond doesn't strike me as very Flemingian). In any case, the bigger issue is that there isn't one version of "Fleming's Bond"--the character changed over the years, going from an intended "blunt instrument" to a very human and very fallible burn-out. The Bond of Casino Royale is a substantially different character than the Bond of You Only Live Twice. I've argued elsewhere that it's more helpful to think of three versions of the character--early, middle, and late Bond. In any case, the filmmakers have gone back to "Fleming's Bond" because it's convenient. Nowadays audiences expect "origin stories" and angst and sturm und drang from movie heroes, and the Bond books provide the basic material for that.

I also slightly sympathize with those who get tired of book-aficionados acting snobbish toward the films. Over the years my attitudes have slightly softened toward Bond films like Moonraker or You Only Live Twice--whatever their demerits, they give spectators their money's worth and provide great spectacles. To some critics, their self-parody is Bondness encapsulated--critics like Pauline Kael considered YOLT "the most consistently entertaining of the Bond packages" (though she admitted that OHMSS would have been the best of them all had Connery starred in it). But her use of "packages" also underscores how formulaic so many of the Bond films are--far more formulaic than Fleming's books, though Fleming worked with a limited set of elements. The majority of the Bond films are pastiches of earlier Bond films--that explains why the recent Craig films have been notable in their departures from the usual formula. To me, the films remain less distinctive and surprising than their sources. But part of Fleming's modern appeal is undoubtedly that his books function as a sort of corrective and supplement to the experience of the Bond films.

I used to argue with Jeremy Duns on whether Fleming would have been remembered if the Bond films had never been made. But now I think the question is beside the point. The films wouldn't have happened if the Bond books weren't strong enough to attract interest from filmmakers, and the films that established the series were deeply engaged with their source novels. In any case, just because something is remembered and popular doesn't imply it was good in the first place. There are many excellent books that are hardly-read and neglected. There are many masterpieces of cinema that are little-seen and deserve a larger audience than blockbusters like Michael Bay's films or popular favorites like Star Wars. So I'm just glad that Fleming's books have found a way of staying remembered.

Jeremy Duns does have a point, of course, though indeed it can be debated: I read an article he wrote on the Johnny Fedora books, and they're - of course - forgotten now. On the same topic, in an English class once, we were asked what was some books which have achieved longevity and I suggested Bond, only for the teacher to suggest that they didn't really count as the films have helped them remain relatively popular. I countered that a Jane Austen adaption every four years has kept her books popular too. (I did enjoy Duns' Free Agent, btw, especially the twist ending of the first chapter.) It's surprising that Eric Ambler has had the screen treatment.

I'd be interested to hear the four stages of Bond, as you see it (or perhaps let me know where you wrote it).

Well said @JWESTBROOK too.

I also think that a few outlandish plots aside, Fleming's plots and villains seem more plausible today in fact. Think North Korea, Putin, maybe Malaysia Flight is under camouflage right now under the Indian Ocean ;)

Yes. I'm puzzled why the film decided to even include the Beretta replacement scene, since it doesn't make sense out of literary context (M being mad at Bond for almost getting killed in FRWL the book) and doesn't have much power without previous knowledge of Bond and M's relationship, which is nonexistent at that point in the film series. That's a case where sticking with Fleming was unwise--the scene should have been saved for a later film.

I'm glad you refuted your teacher (who would have just made me angry)! Nor would the Sherlock Holmes stories have been anywhere as popular without the Gillette play and all the many films made afterwards. Dracula is another case--the stage play and films kept the book in the public eye. On the other hand, there are literary characters who've enjoyed many film/TV adaptations but are now lapsing into obscurity, like the Saint (though attempts are underway to resurrect him for TV). But perhaps there's room for only one Gentleman Hero in pop culture, and Bond now occupies that archetype.

You can read it here: http://debrief.commanderbond.net/topic/51662-the-three-ages-of-bond/

I plan on eventually editing the text and giving it to 007inVT for possible use on his website, Artistic Licence Renewed (http://literary007.com/).

I very much look forward to using that!

Thank you!

His analysis is so insightful albeit, I wonder to what extent Fleming became influenced or threatened by new kids on the block and to what extent did he adjust Bond's character as a consequence?

By the time Fleming died, James Leasor, John Le Carre,Len Deighton, Adam Hall, James Mitchel (aka James Munro) had all launched their own offerings and the genre had started to segment into fantasy and hard nosed realism. This must have had an effect but to the best of my knowledge his view on the explosion in the literary spy market isn't documented anywhere.

Not forgetting James Mayo's (Stephen Coulter's) Charles Hood. Coulter worked along with Ian Fleming at the Sunday Times.

Nick Carter was around early in the "30".

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer bought the screen rights to all the 1,100 Nick Carter stories published in the 1930s. However, all 3 of the films made in the Nick Carter series were based on original stories. (Nick Carter master detective, Phantom Raiders & Sky murder.)

Nick Carter was already around way before James Bond 007 was.

I remember reading one of the later, Bond-influenced Nick Carter books--it was set in Vietnam or someplace similar. Carter's gadget was an artificial fingertip that concealed a miniature gun. That was my last encounter with Nick Carter.

I don't think Fleming was much influenced by the newer spy novelists--from what I recall he dismissed Deighton as Nescafe stuff. His ill-health and depression would not have made him more receptive either. I think that over the years he inadvertently ended up humanizing Bond and giving more of himself to the character. In the last years of Fleming's life Bond might have been a chore, but he was also the most powerful form of self-expression Fleming had left. The impersonal feel of the final book is best chalked up to illness cutting Fleming's writing time in half and leaving him disoriented.

P.S. Thank you for the kind words!

Nick Carter was around early in the "30".

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer bought the screen rights to all the 1,100 Nick Carter stories published in the 1930s. However, all 3 of the films made in the Nick Carter series were based on original stories. (Nick Carter master detective, Phantom Raiders & Sky murder.)

Nick Carter was already around way before James Bond 007 was.

[/quote]

I know. He was originally a P.I., but they changed him to a spy when spy-mania happened in the '60s. Hundreds and hundreds of Nick Carter novels were published between the '30s and, I think, the late '80s.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nick_Carter-Killmaster

Sample text:

"Carter practices yoga for at least 15 minutes a day. Carter has a prodigious ability for learning foreign languages. He is fluent in English (his native tongue), Cantonese, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Portuguese, Putonghua (Mandarin), Russian, Spanish and Vietnamese."

Take that Bond!

And can 007 hope to match Carter's three main weapons? No way!

Carter "has had a series of Lugers, all named Wilhelmina. The knife, Hugo, is a pearl-handled 400-year-old stiletto crafted by Benvenuto Cellini....The third member of the triad is Pierre, a poison gas bomb, which is a small egg-shaped device, usually carried in a pocket but sometimes as a 'third testicle' at his scrotum. Activated with a simple twist, it would, within seconds, kill anybody, or anything, that breathed its odorless and colorless gas."